by Mark Foster

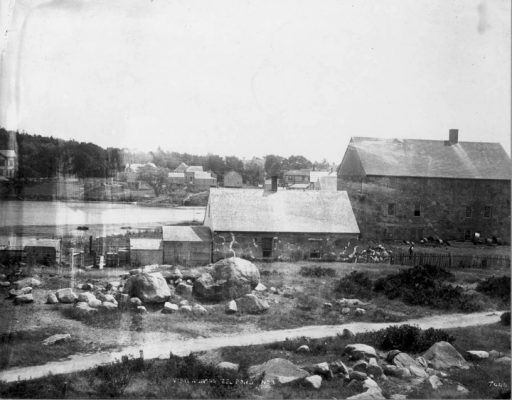

“View Across Eel Pond No. 3” (usually titled “MBL Site”). Photo by Baldwin Coolidge, ca. 1893. Courtesy MBL Archives.

I could tell you stories about the kindness of archivists and librarians, of requests granted for documents so large or lengthy that this now-seasoned researcher blushes to think of them. But my favorite sort of kindness is that in which, while you pour over one item, the archivist quietly mentions that you might also be interested in this other item. Suddenly you are looking at something you didn’t know existed but now find indispensable. Such was the case last spring when I was doing research on the Swift & Co. candle house at Woods Hole.

This old stone building is a landmark of the village. As its date of construction has wandered about, I here set the record straight: though contemplated as early as 1828, planning was not complete until January of 1841 when ads seeking a builder for a stone building “66 long – 46 wide – and 3 stories tall” were published in the New Bedford Mercury. Construction, likely by a New Bedford builder, had begun by June and was near complete by early October when a hurricane unkindly removed the roof and demolished the top floor. The building was probably finished late that fall and in operation that winter.*

Originally the candle house was one of three buildings essential for refining sperm oil: a try or bleach house for the initial boiling of oil, an oil shed for storing oil and a candle house for refining sperm oil and making spermaceti candles. (In the 1840s many refiners were not yet processing “whale oil,” the less valuable oil from baleen whales). Refining itself included the repeated heating, chilling, and pressing of oil over three or four seasons. Though an essential partner to whaling, the refining industry was largely forgotten and left few reminders: of some 60-80 whale oil refineries once in operation, only seven refinery buildings have been identified.

We are fortunate, then, to have this survivor. In addition, we have several early images of the building, among them photographer Baldwin Coolidge’s fine photograph, “View Across Eel Pond No. 3.” Susan Witzell, archivist for the Woods Hole Historical Museum, was kind enough to share a scan of this image. In it Coolidge shows the Swift building as a typical candle house: a large two-story structure on a raised basement with prominent chimney. Below that chimney on the first floor would have been the kettles and hearth used for heating oil and a nearby “taut” press (hydraulic or screw) used for the final pressing of oil. At left would have been several large “slack” presses (screws or levers) used for the first two pressings. Oil drained from the presses to basement cisterns and was run into casks. Candles were probably cast on the second story. Coolidge, however, captured much more than the candle house.

Unlike other sites, after refining ceased in the 1850s the Swift property changed little. When Coolidge took his photo in the 1890s he thereby preserved a nearly intact sperm oil refinery and its landscape. Built on a New Bedford and Nantucket model, the large, formal candle house faces a street at the front of a large, open lot. The try house, where dirty crude oil was boiled (foreground), is relegated to the back, across the “candle house yard” from the oil shed that once stood behind the candle house. Line the yard with casks, add the shed, and we are looking at a sperm oil refinery in the 1840s, the Golden Age of whaling.

This is also one of very few images to show a try house, a building for which, because they were lost in later additions or removed, we have almost no information. Coolidge captured the simple one-story structure with a center chimney that served a hearth and kettles within. While we regret not seeing the front, Coolidge’s photo is unique in showing both a try house and a refinery as a whole.

But the story doesn’t end there.

The high-resolution scan shows the try house windows open and curtained, the double curtain at right hinting at a formal room, like a parlor. To the right are two individuals: a bareheaded man in shirt-sleeves and waistcoat and, near a woodpile, a woman in a long dress, hair in a bun, with sleeves rolled to the elbow.

Here enters the archivist.

I mentioned these domestic details to Susan Witzell. A short time later there appeared in my email a photograph titled “The Old Stone House.” While the photo offered nothing further, Susan wrote that she had always assumed the building was related to the candle house. Indeed, she was right: it is the try house – from the front. It is also the finest image of a try house we have.

Clearly the building once served as a house, for at left is a large doorway in-filled with a later window and small door. With such a large opening, originally that doorway would have been used for casks while workmen used the small doorway at right. Inside, crude oil was pumped from dirty sea-going casks into kettles, heated and then transferred to fresh casks that went to the shed. Further study will reveal more, but by capturing as simple a thing as a doorway the photograph gives us essential evidence toward understanding this rare, elusive building.

Detail from “View Across the Eel Pond No. 3.” The curtained window implies a formal room such as a parlor while a woman and man appear at right. Photo by Baldwin Coolidge, ca. 1893. Courtesy MBL Archives.

Coolidge’s “View of the Eel Pond No. 3” preserved for us a sperm oil refinery much as it originally appeared, offering evidence for understanding both other refineries and the landscapes of the whaling ports. With her thoughtful note, Susan Witzell helped identify the finest image to date of a refinery try house, an image that will help to understand other refineries in general and try houses in particular. This is why I love archivists, those thoughtful people who, living daily with their collections, are able to make connections others can’t and are kind enough to share them with the rest of us.

*See New Bedford Mercury, 3 October 1828; 21 January 1841; 8 October 1841; Daily Atlas, Boston, MA, 5 June 1841; Provincetown Gazette, 23 October 23 1941.