by Susan F. Witzell

Braddock Gifford (1791-1873) worked as a blacksmith in Quissett in the early 1800s. There was a small shipbuilding works there and he made hardware for the small vessels, brigs, barks, schooners and sloops made by shipwright and captain Thomas Fish and owner-investor Barney Marchant at a stone dock built in 1802 on the east side of Quissett Harbor. Gifford owned land on the opposite side of Quissett Harbor and had cranberry bogs along the shore of Buzzards Bay. The prosperity he found as a blacksmith is reflected in his home on Woods Hole Road in Quissett, a handsome center-hall house with a hipped roof (presently 274 Woods Hole Road).

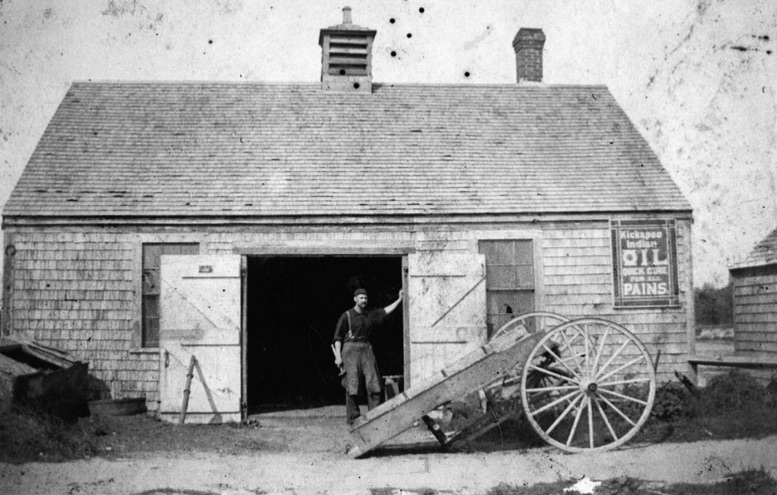

Blacksmith Edward Ward Bragg in the doorway of the old blacksmith shop in Woods Hole on the north side of Water Street with Eel Pond behind it, 1902. The advertisement on the wall at right reads: “KICKAPOO INDIAN OIL. QUICK CURE FOR ALL PAINS.” WHHM

However, the important business of ship building, in this case whale ships, arose in the 1820s in Woods Hole, which had the only local deep-water port. Whale ship owners and investors from Woods Hole and Falmouth (Ward Parker, Elijah Swift and others) developed the Bar Neck Wharf (the present WHOI dock). Support industries for whaling lined the main street of Woods Hole. These included coopers making barrels, bakers supplying hardtack for the long sea voyages, a boat shop making fine whaleboats and the blacksmith making hardware and tools for the ships: iron and steel items not available from mass manufacturing sources in the earliest days. By the 1830s, tools and hardware were beginning to be manufactured in special shops or in factories. Shovels became a mass-produced factory product in the 1840s, just prior to the California Gold Rush. That event made the fortunes of the North Easton, Massachusetts, Ames brothers and their shovel factory.

Gifford moved from Quissett to Woods Hole. His home in Woods Hole, probably an older Colonial dwelling, was at the end of Water Street (across from the current Fisheries complex) and his smithy was up the street near the Eel Pond channel. His family and descendants spread all over Woods Hole and became one of the most important local families, buying up land and developing a large section of Woods Hole from Gardiner Road to High Street.

Besides making ship hardware and whaling tools, Gifford also would have made farm tools, hardware for buildings (latches, locks, hinges, shutter hardware) and cooking tools. He probably worked as a wheelwright as well, forging wooden wagon wheels’ tires made of metal. Nails were made in special nail factories; the most well-known nail factory in this area was the Tremont Nail Factory in Wareham.

Most of us think of the blacksmith as a man who shod horses but this was just part of his profession. Those who specialized in shoeing horses were called farriers. Horses, of course, were the primary means of carrying men, women and children on horseback and in carriages and wagons. Wagons filled the role of trucks, carrying goods and farm produce, and were drawn by horses. Oxen, also shod, were used in teams for heavy draft work, but otherwise horses pulled everything.

The blacksmith softened iron stock by heating it to high temperatures and then forging it into shapes, using a hammer and anvil. A bellows was used to concentrate the heat – an often spectacular sight in a blacksmith’s establishment along with the sparks created by the hammer. The light in the shop was kept deliberately low so the blacksmith could see the color of the heated metal, indicating its hardness.

Gifford had some competition in Woods Hole towards the end of his career and after the end of the local whaling era in the 1860s. The huge Bar Neck Wharf became the location of Sears & Swift, a lumber yard. Its invoices give the names of John K. Sears and Prince D. Swift as proprietors supplying “long and short lumber, mouldings, doors, windows, hardware, brick, lime, cement, drain pipe, paints, oils, etc.” “Horseshoeing & Jobbing, Dealers in Iron, Steel, &tc.” Its premises appear on the 1887 Birds-Eye Map of Woods Hole.

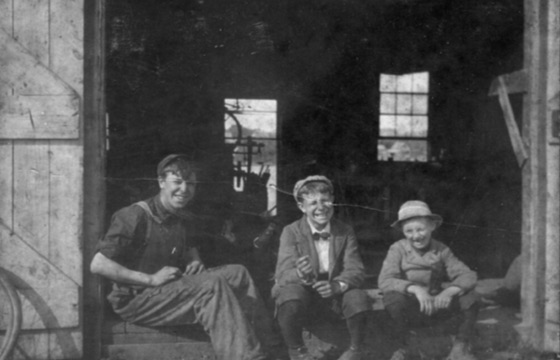

After Braddock Gifford’s death in 1873, the blacksmith next known in Woods Hole was Edward Ward Bragg. In the Gifford family collection there is a photo of the Bragg sons in the doorway of their father’s shop. It is a wonderful, happy photo of boys of the era, Archie Bragg in overalls (perhaps helping his father; this was a common way to learn a profession). The handwriting on the back of the photo’s mounting is a little difficult to read but it seems to say: “Archie, Er—- & Laurence Bragg.” It was this photo, newly cataloged along with the Gifford-Griffin Collection, that inspired the idea for this article.

At some point in the early 20th century, the blacksmith shop building was moved across Main (Water) Street to Dyer’s Dock. It became a heavily used shed for the coal business on the dock. When WHOI bought Dyer’s Dock from Wilbur Dyer in 1957, the old blacksmith shop was moved away and salvaged. It eventually became part of a house on West Falmouth Highway.

For more technical information on blacksmithing, see Old Sturbridge Village’s website (www.osv.org).

Edward Ward Bragg’s sons, sitting in the doorway of the blacksmith shop c. 1910. Archie (in overalls), Er…. and Laurence. These smiling boys were also members of the choir at the Church of the Messiah. Gifford-Griffin Collection, WHHM.