- Introduction

- ES Morse

- Morse in New England

- Morse as an illustrator

- Morse in Japan

- Morse's pottery collection

- Charles Otis Whitman

- Shosaburo Watase

- Umeko Tsuda and Sutematsu Yamakawa

- Katsuma Dan

- Emperor Showa (Hirohito)

- Shinya Inoue

- Osamu Shimomura

- Susumu Honjo

- --------

- E.S. Morse Institute

- Institutional Cooperation

- Fukushima

- About

Umeko Tsuda and Sutematsu Yamakawa

— The Iwakura Mission

From left: Shigeko Nagai, Teiko Ueda, Ryoko Yoshimasu, Umeko Tsuda, Sutematsu Yamakawa, all the girls from the Iwakura Mission, shortly after their arrival in Washington, 1872. Photo from Internet Commons.

In the Meiji’s government’s push to learn from the West, the Iwakura Mission was created in 1871, sailing first to the United States, and then on to Europe to observe and learn as much as they could about the cultures, engineering, science, government, economics, and other aspects of modern life. As part of the Mission, and at the expense of the Japanese government, five girls were carefully chosen to go to America for ten years, living with families, attending schools and colleges, to return to Japan to help the country become fully modernized, and to strengthen U.S. Japan relations. As they left Japan, the Empress personally met with them and asked them to do their very best as representatives of their countrywomen, and to return to serve as role models.

The youngest two of these were Sutematsu Yamakawa, age 10, and Umeko Tsuda, age 7. At first the girls lived together, but their overseers believed that they stayed together too much and would never learn the English language, let alone become an integral part of the culture, so they were separated, moving to different families and different cities.

Umeko Tsuda

Ume Tsuda at Bryn Mawr. Photo from Internet Commons.

Little Ume was put into the household of the Lanman’s in Georgetown, just outside Washington, D.C. Her host father worked for the Japanese legation, and was an expert on Japan. Ume became so acculturated and isolated from her roots, that she lost her native language, and lost all vestige of writing in Japanese. However, she was a bright and quick student, and graduated from the high school, the Arthur Institute in Washington, D.C.

Both girls were required to return to Japan in 1882, Sutumatsu at age 22 and Ume 18. Upon their return to Japan, both girls found that there was no easy way for them to step back into the culture. They were not welcomed in as teachers. Yet both eventually succeeded in bringing the benefits of western culture into the country.

Ume was able to return to America to attend Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania from 1889-1892, where she majored in biology and education. Ume studied right here in Woods Hole at the MBL in the summer of 1891, studying with Thomas Hunt Morgan of Johns Hopkins University. She published a scientific paper about the embryonic development of frogs, the first scientific paper written by a Japanese woman printed in a foreign journal.

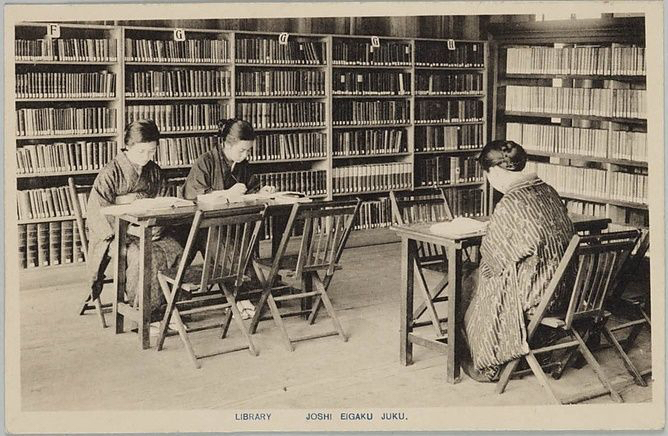

After many struggles tutoring and teaching in other schools, and with the help of Sutematsu, Shigeko Uryo (another of the Iwakura Mission girls), and Miss Alice Bacon (Sutematsu’s American “sister”), Ume was able to establish the Joshi Eigakujuku (English School for Girls) a liberal arts college for girls, with equal opportunity for all women regardless of parentage, an entirely new concept for Japan. It has become known as Tsuda College, and remains one of the most prestigious women's institutes of higher education in Japan.

Students in the Library at the school for girls, later Tsuda College

Sutematsu Yamakawa

During Alice Bacon’s visit to Japan to help establish the Joshi Eigakujuku (English School for Girls) in 1900, from left: Umeko Tsuda, Alice Bacon, Shigeko Nagai Uryo, and Sutematsu Yamakawa Oyama. Photo from Internet Commons.

Luckily for Sutematsu, when the children were separated early in their years in the United States, she was moved to the Bacon family in New Haven, where her brother Kenjiro was studying at Yale. He routinely met with her every Sunday so that she would not lose her native language, and taught her Japanese script and the teachings of Confucius. Several years later, he returned to Japan, and took up a post as assistant professor in the science department of Tokyo Kaisei School (now the University of Tokyo). At the end of her time in America, Sutumatsu had graduated from Vassar as the valedictorian of her class in 1882, the first Japanese woman to receive an American college degree.

Sutematsu married well, and was able to influence society, setting a model of elegance, grace, and beauty, hosting western style events in Tokyo, showing the way for the Japanese people to dress and act in other cultures.