- Introduction

- ES Morse

- Morse in New England

- Morse as an illustrator

- Morse in Japan

- Morse's pottery collection

- Charles Otis Whitman

- Shosaburo Watase

- Umeko Tsuda and Sutematsu Yamakawa

- Katsuma Dan

- Emperor Showa (Hirohito)

- Shinya Inoue

- Osamu Shimomura

- Susumu Honjo

- --------

- E.S. Morse Institute

- Institutional Cooperation

- Fukushima

- About

Fukushima 2011

On March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9 earthquake 80 miles off the northeast coast of Japan triggered a series of tsunamis that struck nearby shorelines with only a few minutes’ warning. The disaster left dozens of villages along nearly 200 miles of coast heavily damaged or completely destroyed.

The waves, some of which measured more than 40 feet, also struck the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant 150 miles north of Tokyo, disabling the plant’s emergency systems and, over the following weeks, resulted in the largest accidental release of radiation to the ocean in history. Because of the plant’s location, much of this contamination washed into the Pacific. Additional airborne radioactive material likely fell onto the sea surface, where it too mixed into the water.

Ken Buesseler, a marine chemist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, with a rosette array used for sampling water at different depths. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

The need to understand the amount, type, and fate of radioactive materials released prompted a group of scientists from the U.S., Japan, and Europe to organize the first multi-disciplinary, multi-institutional research cruise in the northwestern Pacific since the events of March and April. Led by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s Ken Buesseler, a group of 17 researchers and technicians, including two from the University of Tokyo, spent two weeks aboard the University of Hawaii research vessel R/V Kaimikai-O-Kanaloa examining many of the physical, chemical, and biological characteristics of the ocean that either determine the fate of radioactivity in the water or that are potentially affected by radiation in the marine environment.

An international scientific team led by WHOI marine chemist Ken Buesseler completed a research cruise in June 2011 to assess the levels and dispersion of radioactive substances from the Fukushima nuclear power plant and their potential impact on marine life.

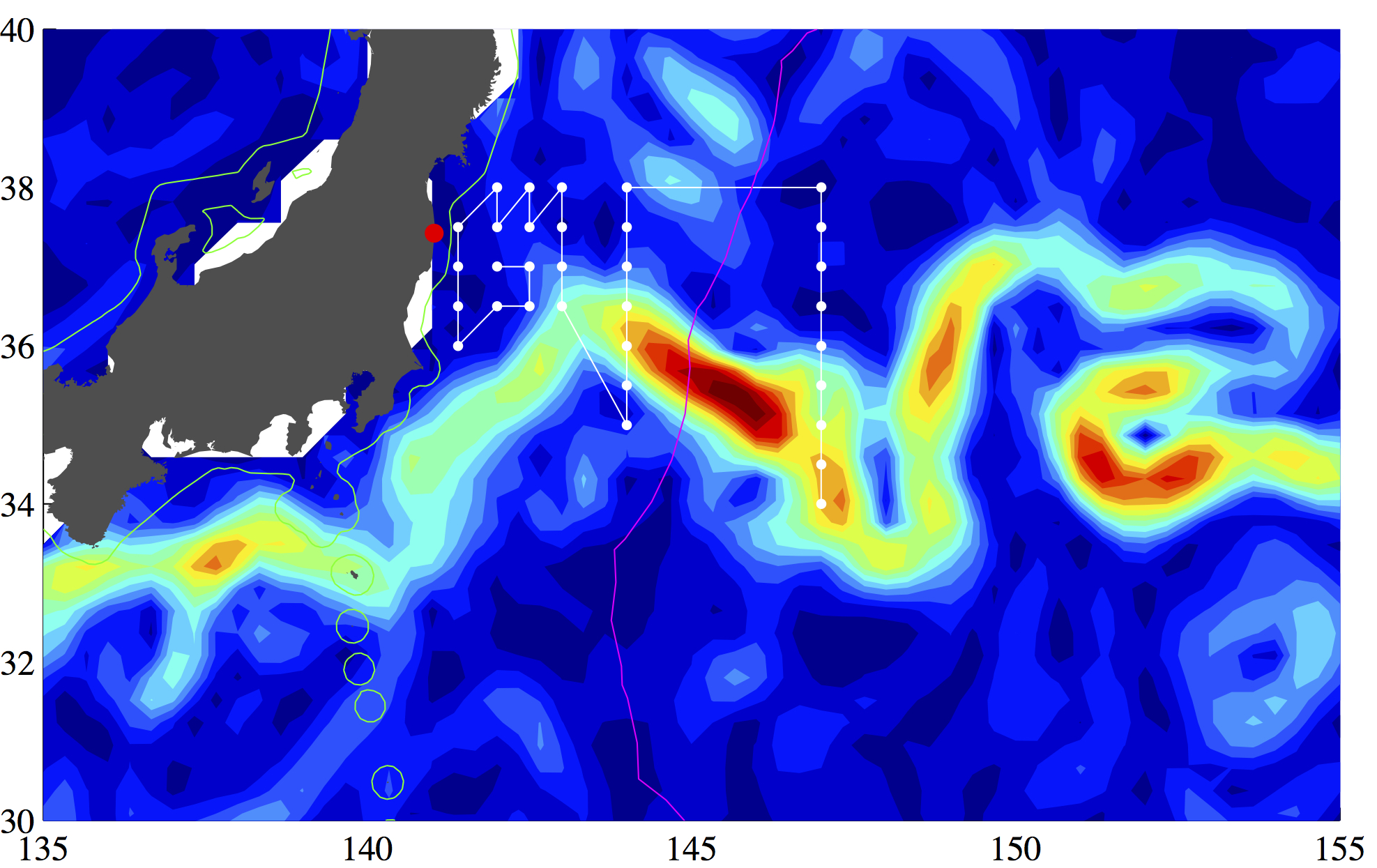

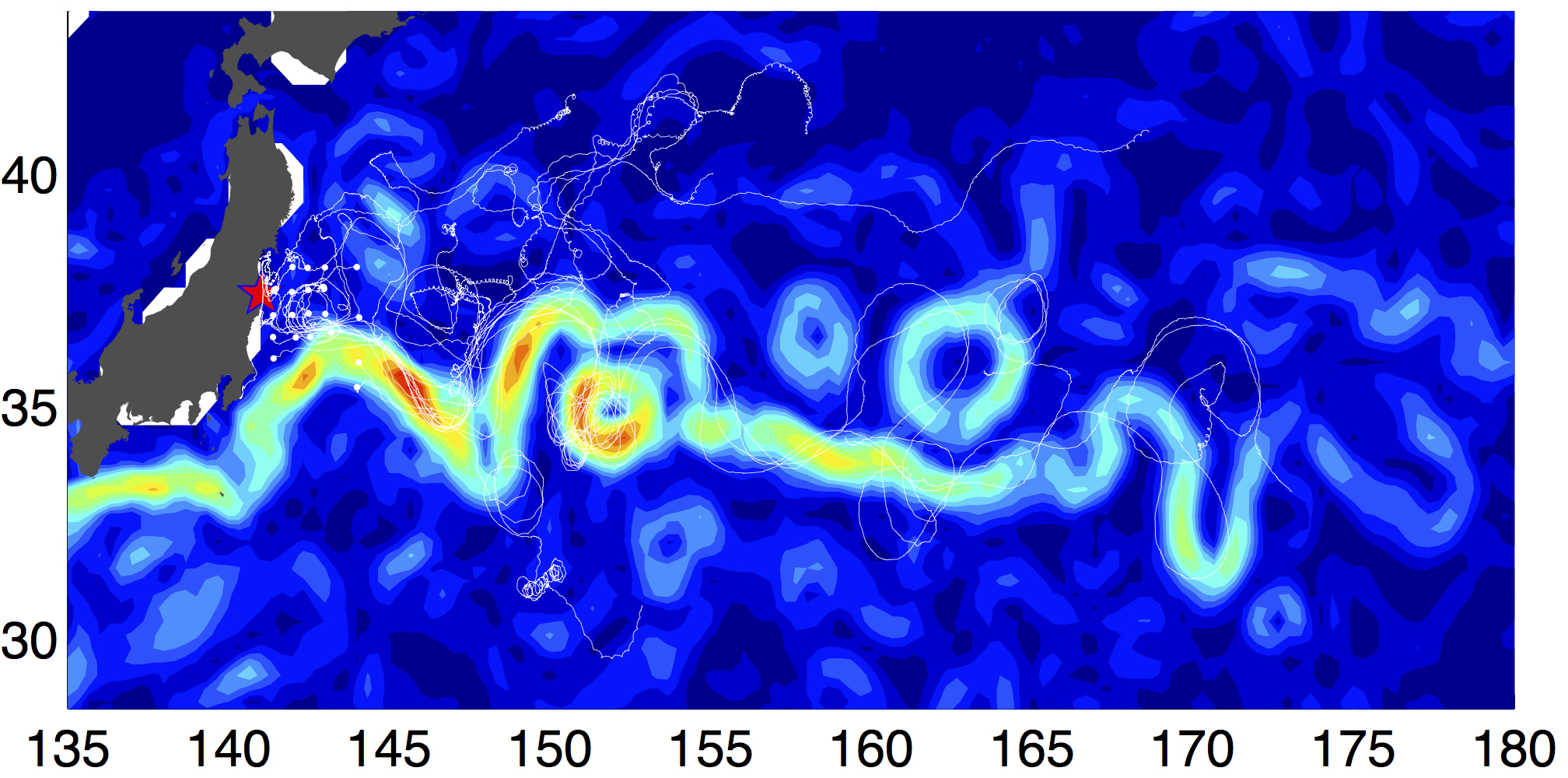

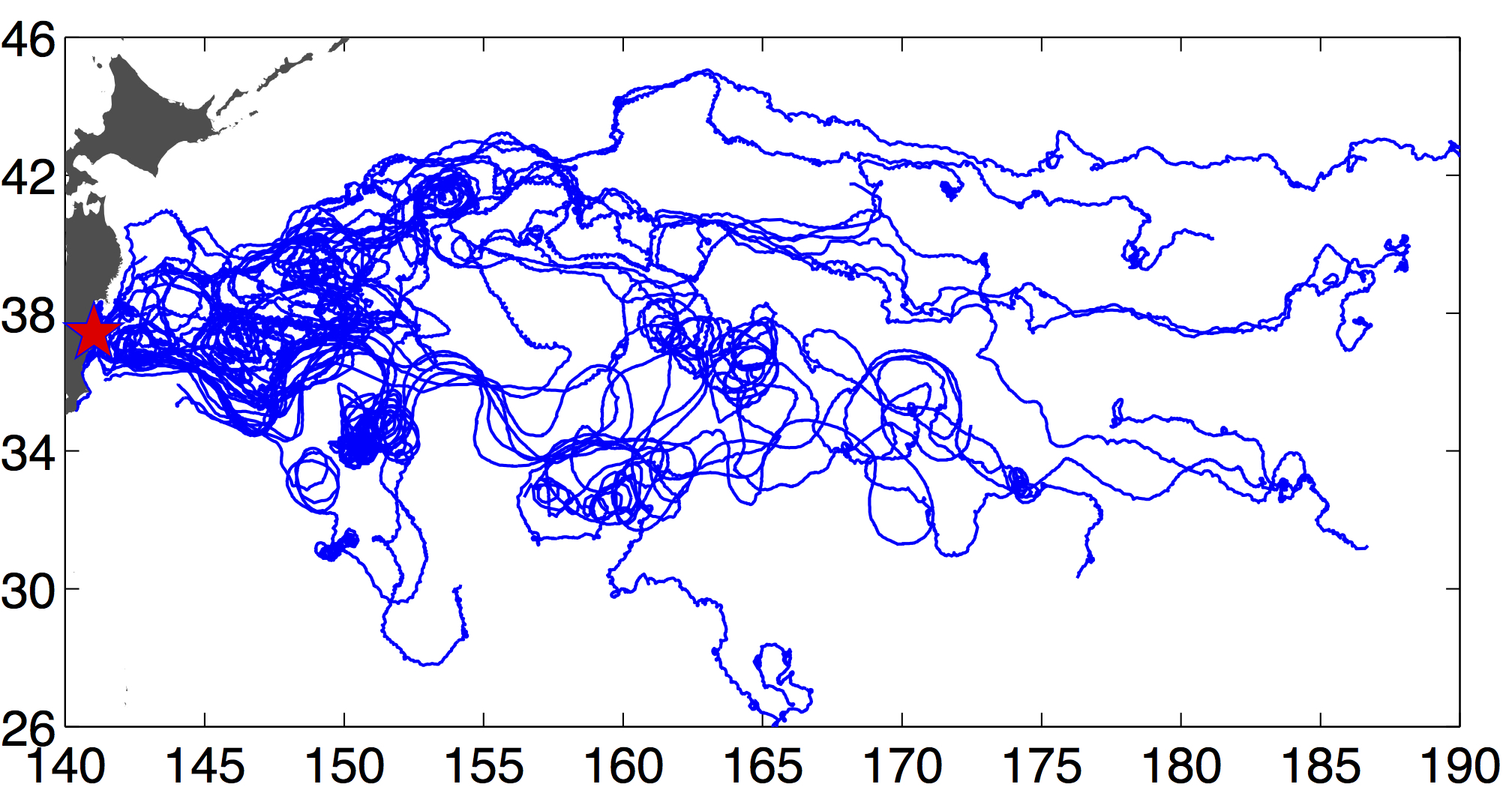

This map and the one above show the sampling stations and cruise track near the Kuroshio Current (shown in yellow and red) Sampling began 400 miles offshore and moved to within 20 miles of the nuclear complex. (Photos by Ken Buesseler, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

After only two weeks at sea in a rigorous and exhausting sampling schedule, the scientists collected:

- More than 1,500 containers ranging from 50 milliliters to 20 liters filled from more than 300 logged sampling events, plus filters of samples as large as 1,000 liters

- More than 3,000 liters of water samples weighing more than 3 metric tons that were shipped to labs around the world after the ship returns to Hawaii

- More than 100 tows resulting in about 50 pounds of biological samples

The samples were then sent out to 16 labs in seven countries to analyze samples for a list of radioactive isotopes that includes cesium-134 and -137; strontium-90; iodine-129; tritium; uranium-236; plutonium-239 and -240; rutherium-103 and -106; radium-223, -224, -228, and -226; and neptunium-237.

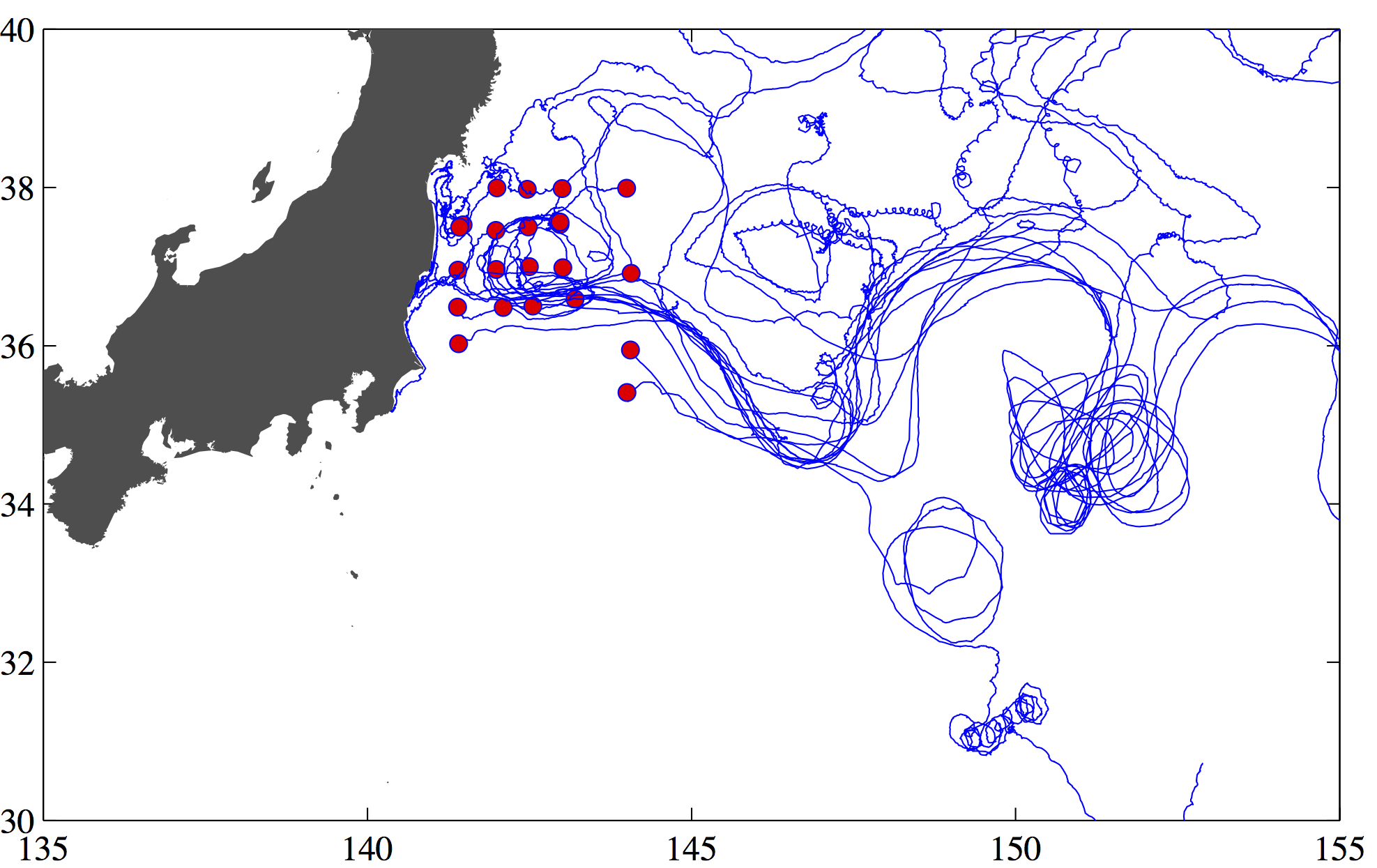

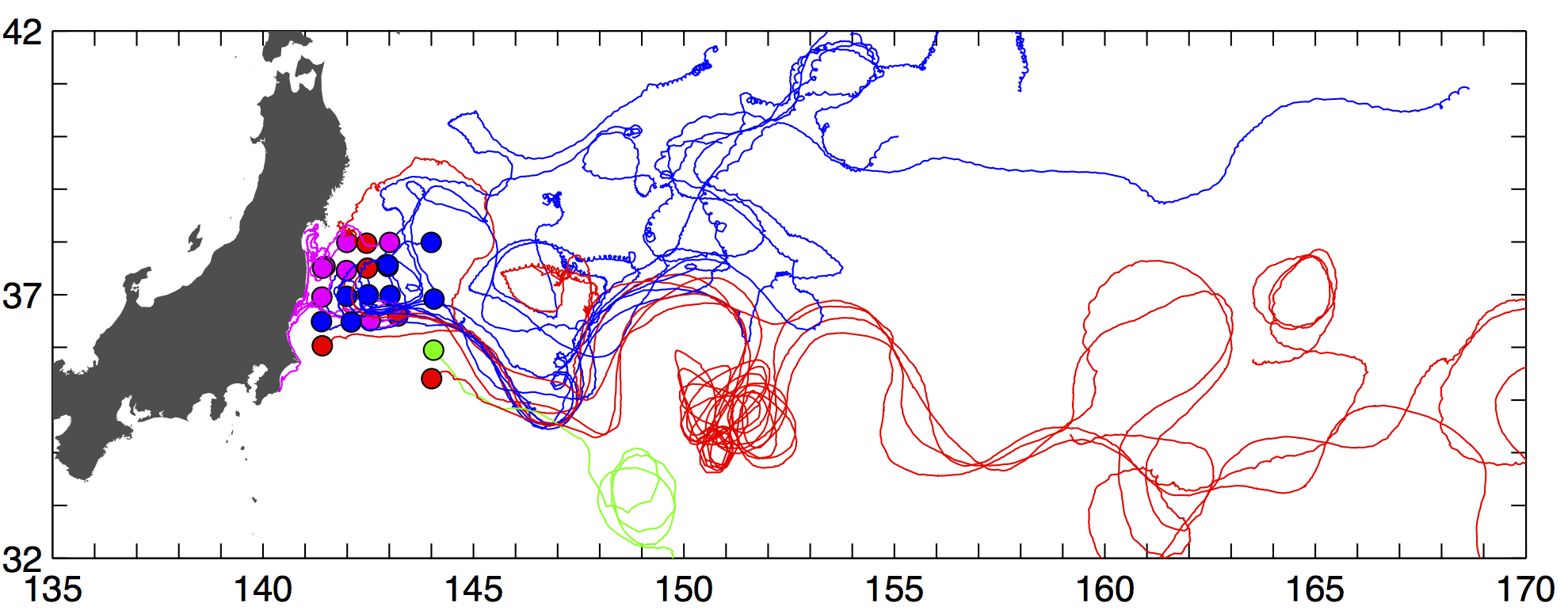

WHOI physical oceanographer Steven Jayne released two dozen surface drifters, which transmitted their locations via satellite while they moved with the ocean currents.

The color-coded track lines from individual drifters, combined with radionuclide data, indicated that the powerful Kuroshio Current acted as both a highway and and a barrier, carrying much of the radiation quickly away from the shore while also largely preventing it from spreading south.

This image and the two above are by Steven Jayne, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.